18 July 2024

Decoding the decade: The time for reform in computing education is now

Decoding the decade: The time for reform in computing education is now

Rethinking computing education: Urgent reforms needed after 10 years of curriculum evolution

September 2024 marks 10 years since the English computing curriculum came into effect. Gone was an ICT subject that was "demotivating and dull" teaching “programs [such as word processors and spreadsheets] already creaking into obsolescence” - as claimed by the then secretary of state for education Michael Gove. In its place computing, a new subject, introducing computer science and programming alongside existing digital literacy and information technology provision.

However, the last ten years have not seen the blossoming of the subject that many had hoped for, with particular concerns about the engagement of girls with the new GCSE. In 2021 the Nuffield Foundation funded a three year project at KCL and the University of Reading to study the impact of the curriculum change (SCARI Computing project). Using case studies of providers with good uptake of the GCSE the project aimed to outline what works for schools in England.

There are reasons for celebration: the GCSE in computer science is now in 80 % of non-selective state secondary schools, with 88,000 students taking the exam in 2023. However, the success of the computer science qualification hides a decline in other computing provision. Since 2012 there has been a substantial decrease in hours of computing taught across secondary schools, with students aged 14-16 seeing their timetabled computing reduced to just 41% of the hours seen before the curriculum change.

The number of other computing qualifications declined to just 73,000 in 2023, making the computer science GCSE the dominant qualification for 14-16 year olds. The reduction in hours taught and the decline of other computing qualifications, combined with girls only making up 21 % of the GCSE CS cohort, suggests that many girls are likely to receive no computing provision at all in key stage 4. This disparity in access to a computing education will further gender inequalities.

Our research involved surveying 5000 students in 15 schools who were successfully delivering the GCSE computer science to large cohorts. As such, the results we found were for some of the best provision in the country. When we asked students why they had chosen the GCSE, girls were more likely to state that it helped with their future option choices than boys, with both genders listing career options as a major reason. Additionally, boys were more likely than girls to give enjoyment of the subject as a reason for taking computer science.

When asking students who hadn’t chosen the GCSE why they didn’t take the subject, nearly three quarters of girls gave “not enjoyable” as a reason, compared to just over half of boys; need matching their career choices was also a major factor for both genders. Statistical modelling of who was taking the GCSE found teacher support and coding attitudes to be major predictors of uptake for both genders, whilst digital making outside school and being from an ethnic minority background were significant predictors for the girls on the course.

Digging into what was taught at key stage 3 computing we found stark differences between girls and boys in terms of their interest in and perceived difficulty of subject topics. Girls found programming, hardware, maths and networking both less interesting and more difficult than boys; whilst at the same time finding project work, digital media and presentation work more interesting. It is worth noting that the topics found less interesting and more difficult by girls make up a good proportion of the GCSE computer science specifications, whilst those found more interesting are better aligned with the previous GCSE ICT qualification.

Our case studies of the schools with best uptake of girls at GCSE level found they shared common attributes: Senior leadership teams valued computing as a subject, with computing departments well provisioned in terms of qualified staff and technical resources, and teachers being supported in accessing CPD that was relevant to them.

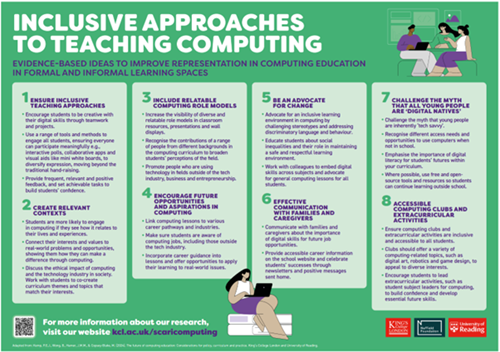

Rather than having a particular focus on inclusive computing weeks or assemblies, whole school inclusion policies were in place, with computing being part of a holistic school model. Lessons were often contextualised to engage the interests of students, with some schools involving the students in defining the topics taught. Teachers were active in picking up and addressing sexist and derogatory language in their classes, building safe and welcoming environments where students felt they could contribute and make mistakes. When role models were used they were from a range of diverse backgrounds and in several cases included school alumni. Where extracurricular activities were present, students were often engaged as subject ambassadors, helping to lead sessions and teach other students.

Whilst these schools were doing better than others in terms of running GCSE computer science classes, there was a strong appetite for subject change amongst senior leadership staff and classroom teachers. There was no particular dislike of individual computer science topics but a recognition that the GCSE and curriculum wasn’t meeting the needs of the students they were working with. One teacher noted that “I personally believe that removing ICT from the curriculum was a big mistake. I think it’s a massively important thing that those children, our children, are taught those skills for how to use Microsoft Office… some kids don’t know how to send an email, and I’m being serious there”.

Not to throw away the great work that has been achieved in getting computer science into the curriculum, our report lays down six recommendations to improve computing education in England. Clearly there are lessons to be learned from the last ten years and there is now a strong case for a substantial review of the computing curriculum and exam landscape. In addition to school based interventions, the explicit inclusion of a broader range of computing topics in a reformed curriculum, the expectation that all students are entitled to regular computing education at key stage 4, and a new computing GCSE that covers a broader range of computing topics would go a long way to fixing the issues we have described above.

The full report can be downloaded here. Additional mini reports and papers can be found here.